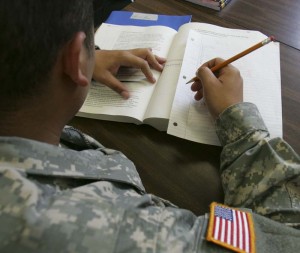

Veterans’ College Drop-Out Rate Soars

In the decade after World War II, 2 million veterans went to college on the new GI Bill, and almost all of them graduated and went on to power the post-war economic boom.

This fall, tens of thousands of Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans are enrolled in colleges and universities across the country, courtesy of the GI Bill. But almost all of them — 88 percent — will drop out by next summer, feeling isolated and frustrated in an alien culture.

Before they disappear from campus, they will contribute to another dismaying statistic: student veterans are seven times more likely to attempt suicide than their civilian counterparts.

“The trend is to hard to ignore,” said John Schupp, a chemist and professor at Tiffin University in Ohio who is spearheading an effort to ease veterans’ transition into academic life.

“For the country to succeed,” Schupp said, “this generation of veterans has to succeed.”

The struggle of veterans to stay in school, and the failure of many colleges and universities to help them, is part of a broader challenge as some 2.3 million veterans flood home from Iraq and Afghanistan to confront a difficult adjustment to civilian life.

Jobs and affordable housing are harder to secure. Many veterans find civilian life pointless and flat after the excitement and stress of war. Families are exhausted from the strain of long separations.

And many vets are trying to manage insomnia, anger, anxiety and depression, common symptoms of combat trauma. A study of veterans in college found one-third had experienced severe anxiety, one-fourth suffered from severe depression and 45 percent experienced “significant” symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Forty-six percent of veterans on campus had considered suicide, compared to six percent among civilian college students. Ten percent of student veterans thought of suicide “often” or “very often,” and 7.7 percent had attempted suicide, according to study by M. David Rudd, clinical psychologist and scientific director of the National Center for Veterans Studies, University of Utah.

Life inside the military is one of tightly shared values and commitments. You show up on time, dressed in the right uniform with the right gear; you are responsible for your buddies and they watch your back. Decisions matter. You respect your superiors and question them only to a point.

In a Marine platoon in Afghanistan, for instance, everyone pays attention during the pre-mission brief; their lives will depend on knowing the plan. But back home in English class, Marine vets may watch in dismay as civilian students may come in late wearing a torn T-shirt and flip-flops, text during a lecture or skip class altogether.

Small wonder that on campus, many veterans feel a sense of vertigo from the sudden loss of community.

“We’re used to high intensity life, constant vigilance on a very routinized lifestyle,” said Cody Nicholls, an Iraq combat veteran and grad student who directs the VETS program at the University of Arizona. “Coming into higher ed is a stark contrast, especially coming out of combat. Here, it’s kind of ‘Here are the keys, good luck, you’re on your own.'”

That’s a key factor that defines the difference between the WWII veterans who attended college and today’s veterans. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, with 13 million veterans pouring out of the ranks and the new GI bill providing free tuition to any four-year college, practically everybody in school was a veteran. Now, with less than 1 percent of military-age Americans volunteering for military service, veterans on campus are scarce and can feel alone.

As a Marine sergeant, Dan Standage relied on his team all the time. But arriving on campus at the University of Arizona, he found “you don’t have a team any longer. That’s what really messed me up; I was sitting all the time in the library totally isolated,” he said. “Having other veterans around is just critical. When you have a bad day you can talk shop with another vet who totally understands you, you can laugh if off rather than take it out on someone.”

Read the full article here.

Leave a Reply